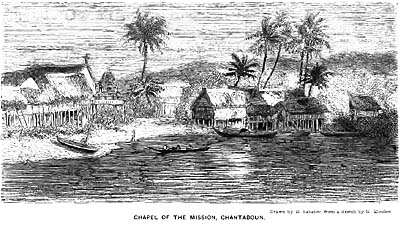

Well equipped with references from high authorities in Bangkok ordering the provincal governors and village chiefs to grant him all support, mainly means of transport as elephants, boats or oxen, Mouhot arrived in Khorat. Despite the references the governor of Khorat refused to help him. For further transport Mouhot needed elephants; when not being given by the governor he had the only alternative to rent some in the surrounding villages, but there he would have to pay a much higher price for them, what extended his budged. He therefore decided to go back to Bangkok first, for demanding stricter orders from there for the governor.

France had an agreement with Siam at the time to be as supportive as possible to all French missionaries and naturalists, as he writes. Siam generally had to grant great concessions to France and Britain to avoid giving them a reason to attack and occupy the country. Baker/Pongpaichit write that all British and French in the Siam of the time enjoyed immunity against the local law, like usually only diplomats do.

An elephant in an elephant camp outside Luang Prabang, close to Mouhot's burial site. Nowadays the praised elephants are merely a tourist attraction. They can not compete with trucks, cars and caterpillars. Image by Asienreisender, 2013

However, Mouhot then made it a second time to Khorat and found the governor now willing to support his needs. From Khorat Mouhot made short trips to Phanom Rung and maybe to Phimai, before continuing his way to Laos.

It's not always easy to identify the places he came to, for their names are mostly different from the names who are in use today. When he came to the area of Sanyabury he describes the travelling in north Laos:

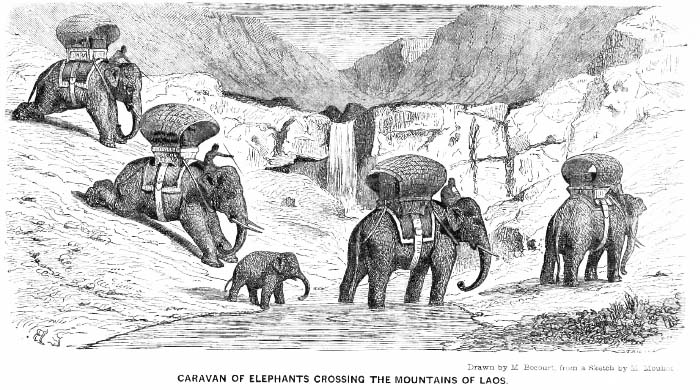

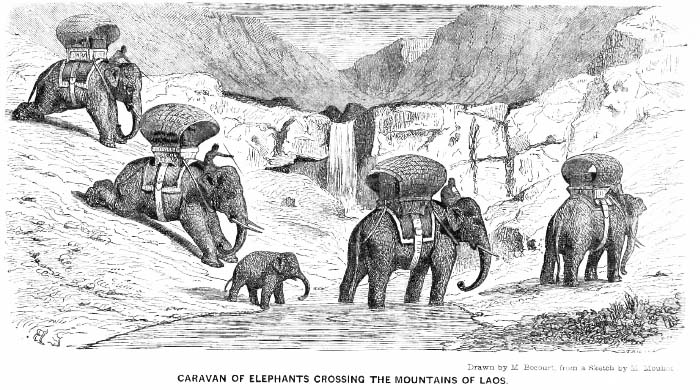

The elephant ought to be seen on these roads, which I can only call devil's pathways, and are nothing but ravines, ruts two or three feet deep, full of mud; sometimes sliding with his feet close together on the wet clay of the steep slopes, sometimes half buried in mire, an instant afterwards mounted on sharp rocks, where one would think a Blondin alone could stand; striding across enormous trunks of fallen trees, crushing down the smaller trees and bamboos which oppose his progress, or lying down flat on his stomach that the cornacs (drivers) may the easier place the saddle on his back; a hundred times a day making his way, without injuring them, between trees where there is barely room to pass; sounding with his trunk the depth of the water in the streams or marshes; constantly kneeling down and rising again, and never making a false step. It is necessary, I repeat, to see him at work like this in his own country, to form any idea of his intelligence, docility, and strength, or how all those wonderful joints of his are adapted to their work—fully to understand that this colossus is no rough specimen of nature's handiwork, but a creature of especial amiability and sagacity, designed for the service of man."

The elephant ought to be seen on these roads, which I can only call devil's pathways, and are nothing but ravines, ruts two or three feet deep, full of mud; sometimes sliding with his feet close together on the wet clay of the steep slopes, sometimes half buried in mire, an instant afterwards mounted on sharp rocks, where one would think a Blondin alone could stand; striding across enormous trunks of fallen trees, crushing down the smaller trees and bamboos which oppose his progress, or lying down flat on his stomach that the cornacs (drivers) may the easier place the saddle on his back; a hundred times a day making his way, without injuring them, between trees where there is barely room to pass; sounding with his trunk the depth of the water in the streams or marshes; constantly kneeling down and rising again, and never making a false step. It is necessary, I repeat, to see him at work like this in his own country, to form any idea of his intelligence, docility, and strength, or how all those wonderful joints of his are adapted to their work—fully to understand that this colossus is no rough specimen of nature's handiwork, but a creature of especial amiability and sagacity, designed for the service of man."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 126

"Designed for the service of man" is not exactly a scientific statement; rather an antrophocentric one, the view through the bible. However, he continues as follows:

With four, five, or sometimes seven elephants, I travelled over all the mountain country from the borders of Laos to Louang-Prabang, a distance of nearly 500 miles.

With four, five, or sometimes seven elephants, I travelled over all the mountain country from the borders of Laos to Louang-Prabang, a distance of nearly 500 miles.

(...)

I soon found that, but for the letter from the governor of Korat, I should have met everywhere with the same reception as at Chaiapume; however, this missive was very positively worded. Wherever I went, the authorities were ordered to furnish me with elephants, and supply me with all necessary provisions, as if I were a king's envoy. I was much amused to see these petty provincial chiefs executing the orders of my servants, and evidently in dread lest, following the Siamese custom, I should use the stick."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 125-129

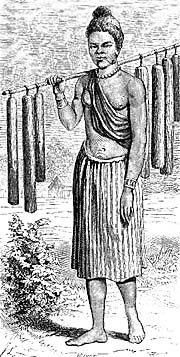

Travelling on elephants. The image is based on a sketch by Mouhot, out of 'Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina'.

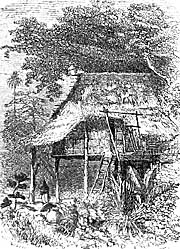

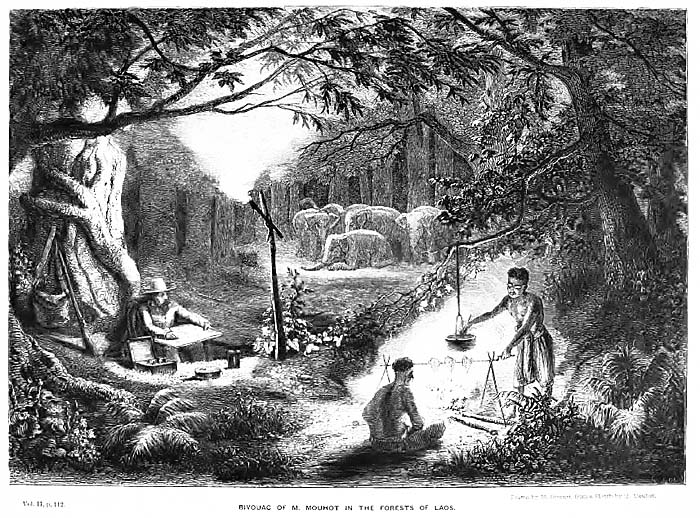

To give an image of the trouble of travelling at the time, he describes the situation when his expedition was compelled to stay overnight in the jungle.

Most of the villages are situated about a day's journey from one another, but frequently you have to travel for three or four days without seeing a single habitation, and then you have no alternative but to sleep in the jungle. This might be pleasant in the dry season, but, during the rains, nothing can give an idea of the sufferings of travellers at night, under a miserable shelter of leaves hastily spread over a rough framework of branches, assaulted by myriads of mosquitoes attracted by the light of the fires and torches, by legions of ox-flies, which, after sunset, attack human beings as well as elephants, and by fleas so minute as to be almost invisible, which assemble about you in swarms, and whose bites are excessively painful, and raise enormous blisters.

Most of the villages are situated about a day's journey from one another, but frequently you have to travel for three or four days without seeing a single habitation, and then you have no alternative but to sleep in the jungle. This might be pleasant in the dry season, but, during the rains, nothing can give an idea of the sufferings of travellers at night, under a miserable shelter of leaves hastily spread over a rough framework of branches, assaulted by myriads of mosquitoes attracted by the light of the fires and torches, by legions of ox-flies, which, after sunset, attack human beings as well as elephants, and by fleas so minute as to be almost invisible, which assemble about you in swarms, and whose bites are excessively painful, and raise enormous blisters.

To these enemies add the leeches, which, after the least rain, come out of the ground, scent a man twenty feet off, and hasten to suck his blood with wonderful avidity. To coat your legs with a layer of lime when travelling is the only way to prevent them covering your

whole body."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 129/130

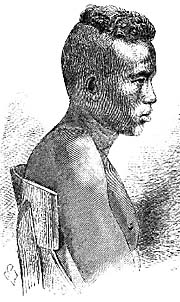

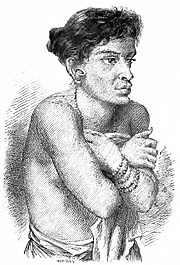

The difference between the Siamese and the Laotians of the time Mouhot described as:

The Laotians much resemble the Siamese: a different pronunciation and slow manner of speech being all that distinguishes their language. The women wear petticoats, and keep their hair long, which, when combed, gives the younger ones a more interesting appearance than those have who live on the banks of the Menam; but, at an advanced age, with their unkempt locks thrown negligently over one temple, and their immense goitres, which they admire, they are repulsively ugly."

The Laotians much resemble the Siamese: a different pronunciation and slow manner of speech being all that distinguishes their language. The women wear petticoats, and keep their hair long, which, when combed, gives the younger ones a more interesting appearance than those have who live on the banks of the Menam; but, at an advanced age, with their unkempt locks thrown negligently over one temple, and their immense goitres, which they admire, they are repulsively ugly."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 134

Thai and Laotians are indeed of the same ethnicity; many of the formerly Tai tribes who lived in their own kingdoms have been included into Siam over history. The incorporation of Lanna in the late 19th century is but one example. The reason that Laos isn't lies simply in the colonial appetite of France in Mouhot's time and later.

Further on he writes:

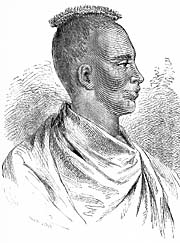

The Laotians have not the curiosity of the Siamese, and ask me fewer questions. I find them more intelligent than either the latter race or the Cambodians, and among the villagers especially there is a curious mixture of cunning and simplicity. They do not as yet seem to me to merit their reputation for hospitality,—a virtue which appeared to be much more practised in Siam. I should never have obtained any means of conveyance without the letter from the Viceroy of Korat, and my experience has been that they are less respectful, but at the same time less importunate, than the Siamese."

The Laotians have not the curiosity of the Siamese, and ask me fewer questions. I find them more intelligent than either the latter race or the Cambodians, and among the villagers especially there is a curious mixture of cunning and simplicity. They do not as yet seem to me to merit their reputation for hospitality,—a virtue which appeared to be much more practised in Siam. I should never have obtained any means of conveyance without the letter from the Viceroy of Korat, and my experience has been that they are less respectful, but at the same time less importunate, than the Siamese."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 139

I am literally pillaged by these petty mandarins and chiefs of villages, and have to give away guns, sabres, lead, powder, colours, pencils, and even my paper ; and then, after having received their presents, they will not put themselves out of their way to do me the smallest service.

I am literally pillaged by these petty mandarins and chiefs of villages, and have to give away guns, sabres, lead, powder, colours, pencils, and even my paper ; and then, after having received their presents, they will not put themselves out of their way to do me the smallest service.

I would not wish my most deadly foe, if I had one, to undergo all the trouble and persecution of this kind which I have encountered.

The Laotian priests are continually praying in their pagodas; they make a frightful noise, chanting from morning to night. Assuredly they ought to go direct to Paradise."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 154

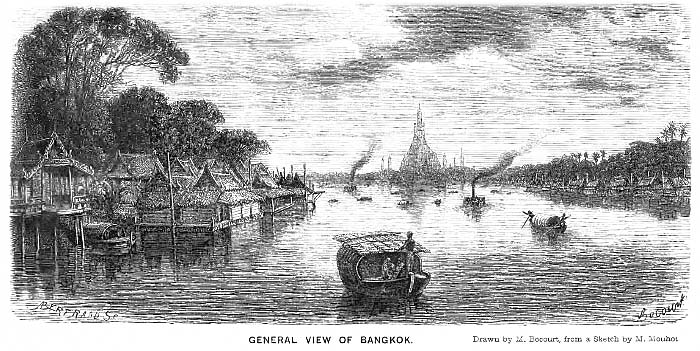

The description of Luang Prabang is disappointingly short. That has probably to do with the fact that his late journals were still in a state of fragments.

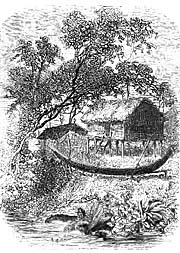

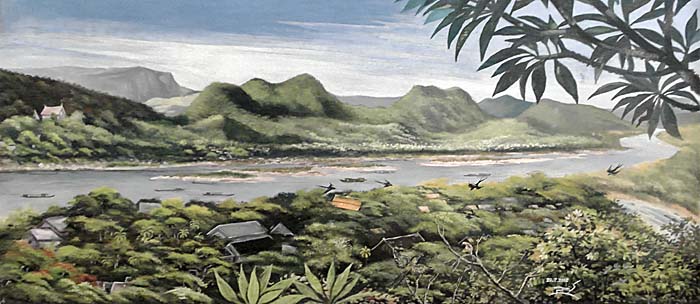

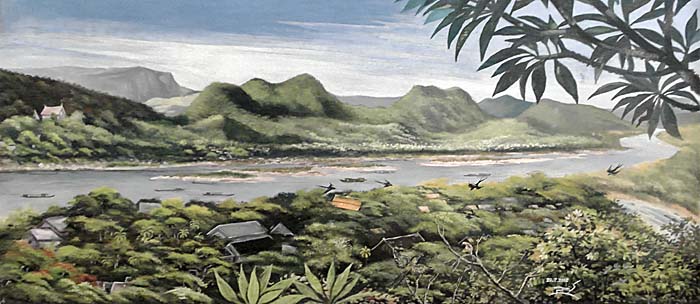

On the 25th of July I reached Louang Prabang, a delightful little town, covering a square mile of ground, and containing a population, not, as Mgr. Pallegoix says in his work on Siam, of 80,000, but of 7000 or 8000 only.

On the 25th of July I reached Louang Prabang, a delightful little town, covering a square mile of ground, and containing a population, not, as Mgr. Pallegoix says in his work on Siam, of 80,000, but of 7000 or 8000 only.

The situation is very pleasant. The mountains which, above and below this town, enclose the Mekon, form here a kind of circular valley or amphitheatre, nine miles in diameter, and which, there can be no doubt, was anciently a lake. It was a charming picture, reminding one of the beautiful lakes of Como and Geneva. Were it not for the constant blaze of a tropical sun, or if the mid-day heat were tempered by a gentle breeze, the place would be a little paradise.

The town is built on both banks of the stream, though the greater number of the houses are built on the left bank. The most considerable part of the town surrounds an isolated mount, more than a hundred metres in height, at the top of which is a pagoda."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 137

A painting of Luang Prabang, showing the confluence of the Nam Khan River and the Mekong River. Seen anywhere in Luang Prabang. Image by Asienreisender, 2013

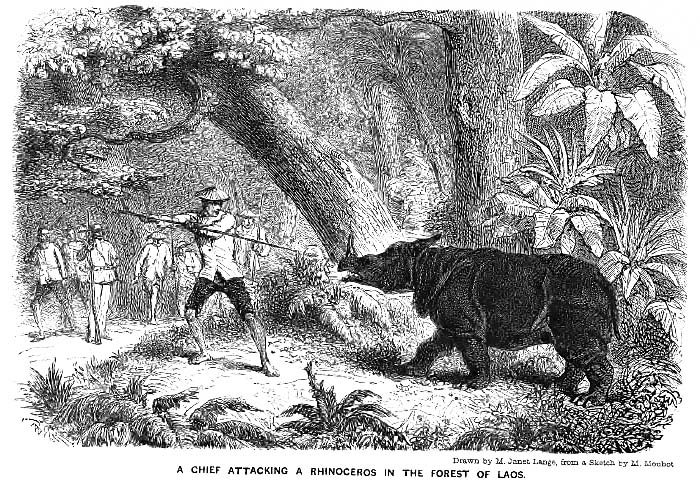

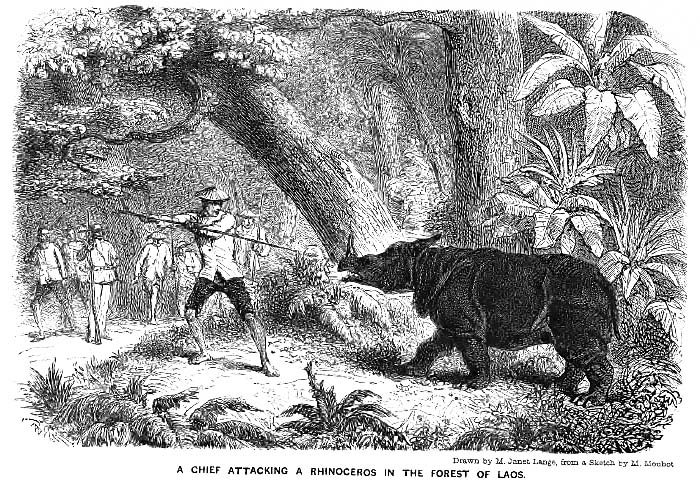

All these 19th century travel narratives contain also some descriptions of hunts. Mouhot depicts several, tiger hunts, a leopard who he shot - and in one of the north Laotian villages Mouhot got an invitation for a rhinoceros hunt. I quote that for it is a rare document and describes not only the BAM-BAM of a western rifle hunt but the way the locals hunted with their traditional weapons. The Indochinese rhinoceros is meanwhile extinct. In 2011 news went around that the last one of the species was killed in Vietnam.

In the hamlet of Na-Le, where I had the pleasure of killing a female tiger, which with its partner was committing great ravages in the neighbourhood, the chief hunter of the village got up a rhinoceros-hunt in my honour. I had not met with this animal in all my wanderings through the forests. The manner in which he is hunted by the Laotians is curious on account of its simplicity and the skill they display. Our party consisted of eight, including myself. I and my servants were armed with guns, and at the end of mine was a sharp bayonet. The Laotians had bamboos with iron blades something between a bayonet and a poignard. The weapon of the chief was the horn of a sword-fish, long, sharp, strong, and supple, and not likely to break.

In the hamlet of Na-Le, where I had the pleasure of killing a female tiger, which with its partner was committing great ravages in the neighbourhood, the chief hunter of the village got up a rhinoceros-hunt in my honour. I had not met with this animal in all my wanderings through the forests. The manner in which he is hunted by the Laotians is curious on account of its simplicity and the skill they display. Our party consisted of eight, including myself. I and my servants were armed with guns, and at the end of mine was a sharp bayonet. The Laotians had bamboos with iron blades something between a bayonet and a poignard. The weapon of the chief was the horn of a sword-fish, long, sharp, strong, and supple, and not likely to break.

Thus armed, we set off into the thickest part of the forest, with all the windings of which our leader was well acquainted, and could tell with tolerable certainty where we should find our expected prey. After penetrating nearly two miles into the forest, we suddenly heard the crackling of branches and rustling of the dry leaves.

The chief went on in advance, signing to us to keep a little way behind, but to have our arms in readiness.

Soon our leader uttered a shrill cry as a token that the animal was near; he then commenced striking against each other two bamboo canes, and the men set up wild yells to provoke the animal to quit his retreat.

A few minutes only elapsed before he rushed towards us, furious at having been disturbed. He was a rhinoceros of the largest size, and opened a most enormous mouth.

Without any signs of fear, but, on the contrary, of great exultation, as though sure of his prey, the intrepid hunter advanced, lance in hand, and then stood still, waiting for the creature's assault. I must say I trembled for him, and I loaded my gun with two balls; but when the rhinoceros came within reach and opened his immense jaws to seize his enemy, the hunter thrust the lance into him to a depth of some feet, and calmly retired to where we were posted.

The animal uttered fearful cries and rolled over on his back in dreadful convulsions, while all the men shouted with delight. In a few minutes more we drew nearer to him; he was vomiting pools of blood. I shook the chief's hand in testimony of my satisfaction at his courage and skill. He told me that to myself was reserved the honour of finishing the animal, which I did by piercing his throat with my bayonet, and he almost immediately yielded up his last sigh. The hunter then drew out his lance and presented it to me as a souvenir; and in return I gave him a magnificent European poignard."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 148/149

A rare hunting scene: a villager is killing a rhinoceros. Image based on a sketch of Mouhot. Source: 'Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina'.

Mouhot caught eventually malaria and suffered for some days of heavy fever, had a strong headache and then lost more and more senses. He tried to continue his journal, but became too weak for it. The last entries were:

15th October. 58 degrees Fahr.—Set off for Louang Prabang.

15th October. 58 degrees Fahr.—Set off for Louang Prabang.

16th.—

17th.—

18th.—Halted at H . . . .

19th.—Attacked by fever.

29th.—Have pity on me, oh my God . . . . !

These words, written with a trembling and uncertain hand, were the last found in M. Mouhot's journal."

Mouhot, Henri:

Travels in the Central Parts of Indochina,

London 1864

Volume II, p. 160

The last sentence is not written by Mouhot himself but probably by his brother Charles, who cared for the heritage.

The tomb of Henri Mouhot at the riverbanks of the Nam Khan. Image by Asienreisender, 2013

Henri Mouhot died at November 10th, 1861 at the banks of the Nam Khan River in north Laos, some ten kilometers outside of Luang Prabang. He was burried there in the European way. The Laotion way of the time was to hang corpses into the trees. The wild animals would feed then from them.

Mouhot's reliable Siamese servant Phrai brought the traveller's belongings after the burial to Bangkok.

Nowadays there is a white tomb placed at the banks of the Nam Khan River. It's in a quite good shape. I am not sure if that is exactly the place Mouhot has died. Additionally there is a statue of him placed, where he looks like an old man. Before there was an older monument, built in 1867, which was destroyed in a flood.

Meanwhile Laos is changing in a rapid development like it happened a few years ago in China. The old road parallel to the river is under construction and close to the grave a new bridge is under construction as well. Soon it will be more and more noisy around the grave.

A new bridge over the Nam Khan River under construction, accompanied by two roads on both sides of the river. Laos' industrialization is going on rapidly.

March is the peak of the dry season; the river has it's lowest water level, and the air is poisened with dense smog - a result of countless forest fires.

Image by Asienreisender, 3/2013