1.

An Early Civilization

Dvaravati was a loose network of city states on parts of the territory what is nowadays Thailand. The Dvaravati Culture is the artistic expression of this civilization, which can be traced back to roughly the 6th century CE, although there are indications of a proto Dvaravati Culture in U Thong which evolved already in the 2nd century.

A Dvaravati scultpure, unknown date. Image by Asienreisender, National Museum Lopburi, 12/2012

It was a Buddhist culture which was dominated by the Indian ethnicity of the Mon People. The Dvaravati Culture neighboured the emerging Khmer empire of Angkor, which spread out with it's military apparatus over large parts of Indochina and ursurped the Dvaravati city states in nowadays central Thailand in the first half of the 12th century.

The name Dvaravati comes from the Sanskrit engravement of the name of a king Sri Dvaravati in two silver lockets, who were found in Nakhon Pathom at the restoration of Wat Phra Pathom in 1853. Dvaravati is translatable to the phrase 'Which has Gates'. Relates certainly to a fortified place; Nakhon Pathom was a fortified town, surrounded by a trench and of a size of 3,700m length and 2,000 meters width.

Mueang Fadaet in Kalasin Province / Isan was a medieval Dvaravati town which dates roughly 1,000 years back. It was 171 hectars large and surrounded by a trench and a city wall. Quite a number of border stones with for the Dvaravati typical engravements were found around here. There is a small museum nearby in which a few pieces are displayed. The museum is sparsely frequented; a woman opened it exclusively for me when she saw me approaching. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, 11/2015, 2016

2.

A Network of City States

A number of city states were part of the Dvaravati network, among them Nakhon Pathom, Lopburi and U Thong in central Thailand. On the Khorat Plateau in the alluvial plains of the Chi River and the Mun River was another center of the Dvaravati Culture as for example that of Mueang Fadaet at Kalasin and another place at Nakhon Ratchasima. Dvaravati may have stretched out northwards as far as nowadays Vientiane. In Lamphun, nowadays north Thailand, coexisted the Mon culture of Hariphunchai which lasted longer than the both others, who were absorbed into the empire of Angkor. All three regions were part of the Dvaravati Culture, although there were, besides the common ethnic and cultural roots, also regional differences between them.

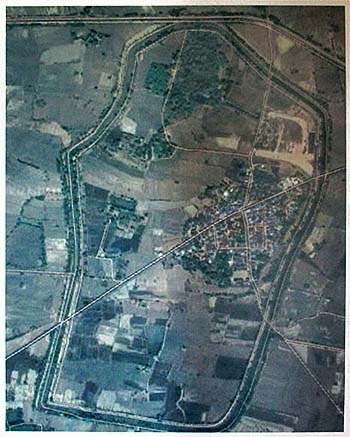

The medieval town of Mueang Fadaet in an aerial photograph. The trench is still intact, the city wall no more. A new village lies on parts of the ground of the old city; the rest is nowadays mostly rice paddies. An extended canal system was in and around the place. Image by Asienreisender, Kalasin, 11/2015

Most of the Dvaravati towns were surrounded by a round or oval city trench. Others, like Lamphun, had the shape of a sea shell. The coastlines of the Gulf of Thailand differed in that times; some of the towns were coastal cities, all the others were situated at river banks, what was compelling for towns in premodern times. The access to water was crucial for peoples lifes; besides, rivers served as the earliest transport routes before the construction of the first long overland roads. Additionally were larger canal systems for irrigation purposes in and around these cities installed. Since the canals and trenches required a centrally organized workforce, we can certainly assume that these towns were under the reign of a strong central power which used slave work and/or forced labour of large parts of the population to achieve these installations. In return, the agricultural productivity became much higher than as it was in former times. That led to a growing workforce and could feed also a growing army.

So, for any early civilization the irrigation system was the basic condition for a growing population. Once the workforce was recruited and the irrigation basically installed, the surplus workforce could be used for other purposes. That were usually then city walls and temple constructions. The Dvaravati Culture created a number of smaller and larger Buddhist monuments, who were built on a laterite fundament and then extended with brick constructions. An example for a typical Dvaravati Buddhist temple is Wat Chama Thewi in Lamphun.

It's probable that the Dvaravati towns were placed along an ancient trade route, starting in India and Burma, crossing the Tenasserim Mountain Chain at the Three Pagodas Pass into Thailand, touching the shores of the Gulf of Thailand, turning northwards along the Chao Phraya River onto the Khorat Plateau and continuing to south China (Yunnan) and north Vietnam.

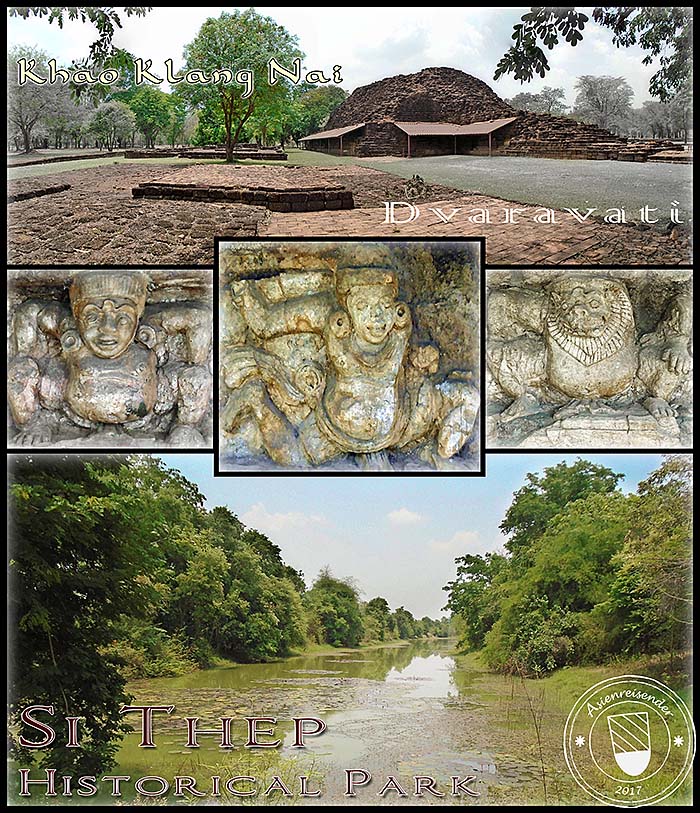

Khao Klang Nai is a Buddhist monument of the Dvaravati Culture in Si Thep (see: Si Thep Historical Park). It's almost 45m long and 29m wide, with a height of 12m. In it's original state there was supposedly another structure on top of the monument which disappeared under the tooth of time. Remarkable are the few stucco motives who are left.

Si Thep was a large twin-city, surrounded by a wide moat. Inside, paralleling the moat, was a city wall of which a small mount, overgrown with trees and shrub, is left. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, Phetchabun Province, 4/5/2017

3.

The Indian Roots

Since the Mon People are of an Indian ethnicity, they brought their cultural foundations from India. The language of the Dvaravati inscriptions, who are left in the remaining buildings, is Sanskrit and Pali. The Dvaravati Culture was following a Buddhist doctrine, although some Hindu influences were included. Buddhism came, of course, from India to Southeast Asia, and all the arts and architecture of the time had Indian roots. In the Dvaravati towns were also coins minted, a technique which also came from India to here. The concepts of the state and the political organization were certainly also of Indian origin; there is little doubt that we have it to do here with another Oriental despotism.

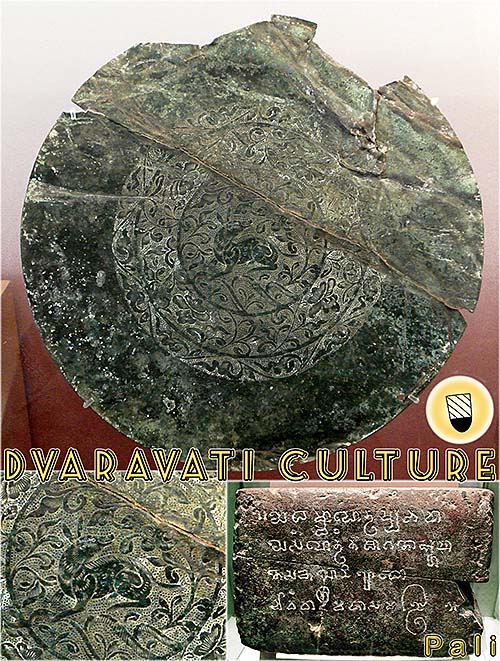

Dvaravati art and culture. A bronze or copper plate with an animal (seems to be a dog), surrounded by plant motives and a Pali stone inscription. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, National Museum of Lopburi, 12/2012

The Dvaravati Culture played an early key role in the introduction of Buddhism and Buddhist arts into Southeast Asia. Dvaravati art has it's very own style on one hand and is clearly distinguishable from Khmer art or that of the Srivijaya empire on Sumatra; on the other hand it is close to the art and culture of contemporary Thailand as garudas, nagas, Buddhas and other religious items were displayed in the temples as they are still today. The prefered material for sculptures was only seldom the sandstone the medieval Khmer used, but mostly a certain, hard limestone, a compressed chalk which is to find in the quarries east of Lopburi and southwest of Ratchaburi. The stonemasons carved excellent works out of that material, while they worked rarely with bronze, and their bronze castings were usually of a lower quality. Seems, they didn't have good access on bronze (respectively copper and tin) as a raw material.

The 'thammasat', on which the ideal moral and social concept of the just ruler is based, was a Dvaravati derivation of an older Indian concept. It was, by the way, still the basic concept of the absolute monarchy of the Siamese kings of Ayutthaya, adapted from Brahmanist influences from Angkor. Moreover, it still plays a role in the legitimation pattern of the Thai monarchy.

4.

Occultation

Generally we know very little about the Dvaravati Culture. As it is with other earlier Southeast Asian civilizations, there are no written sources left exept stone carvings in temple sites or on tablets. All what was written on palm leaves, the 'paper' of the time, has been rotten away in the humid, tropical monsoon climate, or has been destroyed in war times. However, as well as it is at the examples of Funan and Angkor, there is a bit of a written record on Dvaravati, documented by ancient Chinese visitors.

The Dvaravati Culture in central Thailand and on the Khorat Plateau became eventually victim to the Khmer empire of Angkor. Central Thailand was conquered by the Khmer in the first half of the 12th century, under king Suryavarman II, the pompous godking who ordered the construction of Angkor Wat as his personal graveyard. That set an end to the Dvaravati in Nakhon Pathom, U Thong and Lopburi. The northern 'branch' of Dvaravati at Hariphunchai lasted until the late 13th century, when it was incorporated into the Tai kingdom of Lanna.

The Dvaravati Culture in central Thailand fell victim to the military expansion of Angkor in the first half of the 12th century. That happened in the reign of king Suryavarman II, who's graveyard is Angkor Wat, which was built at the same time. The Dvaravati Culture on the Khorat Plateau shared the same fate. Only the northern Dvaravati Culture of Hariphunchai survived the expansion of the sinister Khmer empire. Hariphunchai was conquered in the 13th century by the Tai empire of Lanna in the time of king Mangrai. Image by Asienreisender, bas relief of the Bayon, 9/2015